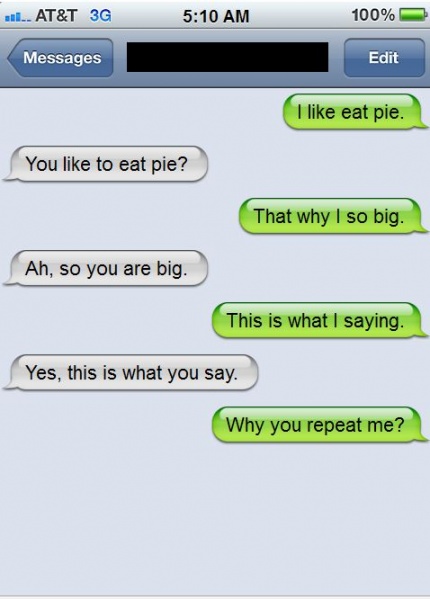

The wrong way to help someone…

Recasting is a form of error correction from a teacher to a student; uptake is how the student reacts to this.

Basically, recasting is when the teacher repeats what the student says but in correct English. Uptake is when the student hears the correction and repeats the phrase.

This is an example of recasting in action:

Student: Yesterday I go at the park.

Teacher: Ah, you went to the park yesterday.

Student: Yes, I go at the park yesterday.

What happens here is that after the student made a mistake the teacher essentially repeated the student’s utterance but in correct English.

Recasting is very common in classrooms (and one of the most popular ways a teacher will correct an error) with some studies suggesting that over 50% of error correction in class was in the form of recasts.

There are several things to note here. Firstly in the example above the student makes 2 mistakes (the verb form and the preposition) and the teacher corrects both.

Secondly, in this case, after being corrected the student does not self-correct. In other words, there is no uptake which is the term used to talk about whether a student recognises they have made an error and realises that the teacher has corrected it.

Lack of uptake is very common and in many cases the student will assume that the teacher is just responding naturally to their comment and not correcting them at all. This is especially true when the lesson is content based and not a more formal language or grammar focussed lesson where the students are aware that they are being corrected.

Again, studies have suggested that about 50% of recasts are essentially ignored by the student (i.e. there is no uptake) although it has been found that students who are listening to the conversation between the teacher and the student will pick up on the recast and the error more than the actual student themself.

So there are both positive and negative arguments to be found in recasting:

Positive

- It is a relaxed way to correct and doesn’t highlight the error and possibly embarrass the student.

- It doesn’t generally interrupt the conversation.

- Listeners to the conversation can pick up the recast.

- It works far better with adults who are more aware of and responsive to it.

Negative

- Most recasts are ignored; the student participating in the interaction does not always pick up on the recast.

- Does not work with younger learners.

- If the student makes more than one error in an utterance, the teacher will correct all the errors which could lead to overload.

- Students can get frustrated when they are trying to talk and feel they’re constantly being interrupted by recasts.

Conclusion

Should you use recasting? Opinion varies. Some studies suggest that it works and should be used extensively, others say that it is not useful. Given the situation above perhaps the ideal class for casts would be a formal grammar lesson with adults; the least ideal class would be an informal chat lesson with young learners.

One approach would be to correct in a slightly more formal manner. This can often have very beneficial effects:

Student: Yesterday I go at the park.

Teacher: Remember, the past tense of go is went.

Student: Ah, ok. I went at the park yesterday.

Teacher: Good.

Notice there that the teacher did not correct both mistakes but just the most important – another important tip to remember.

Reference

Most of the statistics here come from Lyster and Ranta (1997). There is also a more formal discussion of recasts by Victoria Russell of the University of South Florida called Corrective Feedback.

0 Comments